Octopus's Garden

Originally, I'd planned to say that this green, yellow, and white quilt top would go down as the hardest quilt I've ever done. I've had a lot of time to think about that statement (more about that in the course of this post) but I realize, even now, that is not an accurate statement. There is a difference between a pattern that is painstaking, and a pattern that is hard. I do not consider those terms interchangeable.

The "swirl" pattern is an old one. No idea on who originally made it, but it's been around a long time. I first encountered it in All Quilt Blocks Are Not Square, by Debra Wagner, where it was called "Candy Swirl." I eventually tracked down two blog posts by Barbara Brackman, which provide some evidence that the pattern has been around, albeit rare, since around the 1890s:

- http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2010/02/mystery-pattern-swirl.html

- http://barbarabrackman.blogspot.com/2010/02/more-on-swirl-design.html

All Quilt Blocks Are Not Square contains a template you can trace and use, and Ardco templates offers a metal template you can purchase. (I am working from the Ardco template.)

I can find very few examples of this quilt actually being made:

- One is red and white.

- One is purple and white and another on that page is multicolored.

- One is multicolored.

- One is brown.

That's not many examples, and I can understand why few people have tackled it. Those curves look really, really nasty. I will admit that a few years ago, I tried to machine-piece the block and created a ragged, miserable failure that was better not discussed or shown to anyone except my cat. I put the template away and muttered, "Someday. Someday I will PROVE that I can do this pattern."

It's doable. My technique was wrong.

When I learned that a coworker and his wife were expecting their first child, I remembered his love of all things tentacly and pulled out a set of sea-creature fabrics to show him. He gravitated to the yellow-green and white fabric a mutual coworker/friend had given me as a gift, part of Tula Pink's Salt Water line. I didn't notice the title of the pattern until much later.

The requested image size is not available for this photo on Flickr (uploaded when this size was not offered yet). Try another size or re-upload this photo on Flickr.

I can't articulate why I went to this pattern piece after having it stored for so long. Maybe it made me think of tentacles. Maybe it made me think of drifting seaweed. Maybe I just wanted a challenge. I've been itching to push myself, to challenge my skillset, and I decided it was time. I remembered my disastrous attempt to machine-piece the pattern, and opted to do this one by hand. To me, that implied English paper piecing, which I'm very comfortable with after a few projects; it's great for accuracy, but I'd never done it with curves. No EPP templates for this pattern exist, so I chose to make my own.

First, I used the template to roughly cut out each piece from the fabric. I had success with leaving the 'foot' of each piece unusually long, to facilitate trimming:

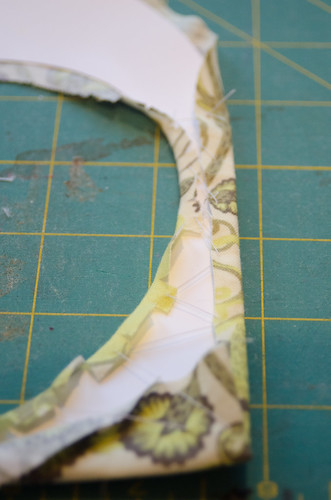

I bought a single sheet of Mylar from a craft store, and traced the finished size of the piece onto the Mylar with the finest-tipped Sharpie I had. I made four, and numbered them so I could keep track in case any of them proved problematic. (They didn't.) Using Mylar instead of paper meant I had a semi-permanent piece, and permanent as long as I was reasonably careful; I did not want to make more pieces than absolutely necessary. Cutting accurately is essential for the pieces to fit properly. Here's what the same piece looks like with the Mylar template overlaid:

The next step is to get the fabric to conform to the template, and I realized I needed a hybrid approach. The top outer curve, the 'head' of the swirl, could be done drawstring-style, like this:

Being a perfectionist, I felt that everything came down to having a sharp, perfect point where all four swirls met in the center, so I started there. I made a quilter's knot with my thread, folded the fabric over the point, and made a single backstitch to secure the point. I would then do a very loose running stitch down the head of the piece, until I reached the section I thought of as the "neck" of the piece. At that point, where the piece began to narrow, I would work back and forth, using a technique I've always called "corset lacing" in my head. I need the lines to be far enough apart that I can handstitch around them without frustration, but I need the pieces to reasonably conform to the template and hold steady. When fully corset-laced, it would look like this:

Those inner curves are problematic, though; there's one on the underside of the head, and one at the foot of the piece. I liked having big seam allowances to make sure I had enough room to trim the piece down afterward, but big seam allowances and inside curves do not mix; when corset-laced, they won't adhere tightly to the template unless you clip the curves. Accept this. If you're doing this pattern, you ARE clipping curves. I do not believe this pattern can be done without it:

I would lace up four pieces, and start fitting them together to make the square, anchoring each one in place, one at a time, and hand-sewing them together:

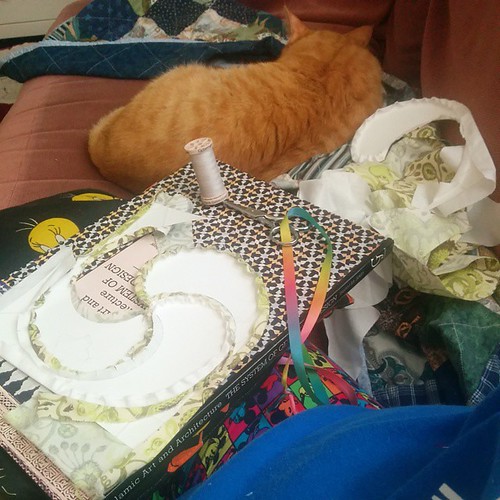

Work on the swirly #quilt continues. Kolohe supervises with his eyes closed.

Work on the swirly #quilt continues. Kolohe supervises with his eyes closed.

(Kolohe is, of course, supervising.)

I would lay the wrapped templates flat on a book (the one shown is the widest and lightest book I have) and fit them together with my hands, then stitching back and forth to anchor the fabric together. My needles won't pierce Mylar, so it was easy to not stab the templates. Once all four pieces were done, I'd flip the piece over, verify I had a razor-sharp center point and good clean curves, and then remove the basting thread and template pieces for reuse. (Basting thread from the previous square became sewing thread for the next square. This paragraph also glosses over the triumphant slapping of the finished block onto my design wall, but that's a personality quirk you may or may not share.)

I will say from the outset: this method is slow. Very slow. From cutting to lacing to fitting to sewing to removing basting thread and template, each piece took me about 90 minutes to complete, but I rarely had to redo anything except the last few stitches of the 'foot' of the piece. Leaving extra-long bottom and exterior seam allowances left me with pieces that looked ragged, like this, but were clearly accurately pieced:

Because I am batshit crazy that's why!

Because I am batshit crazy that's why!

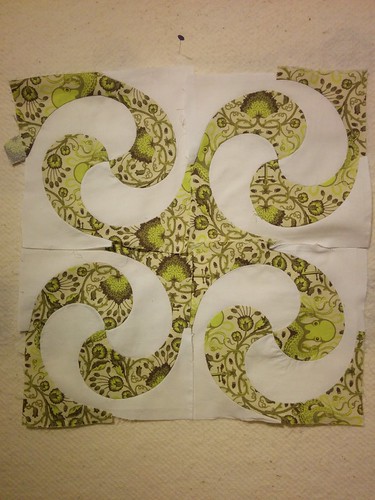

When I completed the first four, it was clear that even with ragged edges, I had an accurate set of templates and could proceed:

Raw edges but a decent demo of four blocks, untrimmed

Raw edges but a decent demo of four blocks, untrimmed

I've been very careful with my fabric pressing, removing the basting threads so the seam allowance could flip in either direction, and pressing as much of the seam allowance to the dark side as possible. I then took my square ruler and marked the finished size of the square with a pencil, making sure the center of the finished piece was absolutely in the center of the square. After pressing and marking, I trimmed the seam allowances down to my standard quarter-inch.

I realized something at this point, though: I needed a dismount. I didn't think I wanted the pattern to cut off at the edge of the quilt, so that meant I needed a set of special squares -- ones that only had one green swirl and three white, to finish off the interior figures without starting another at the edge. I went back to my Mylar and carefully traced out one more pattern from my template -- one that had the equivalent of two swirls joined together instead of just one. I suspected it would save me a decent amount of labor by removing one curved seam, and I was right; the border pieces take me a little closer to 60 minutes to make instead of the 90 for a four-swirl square.

Once I'd made a few border pieces, I pressed, marked, and trimmed a few border and interior pieces so I could have the reward of seeing them all come together, and it was intensely encouraging to see clean swirling lines emerge:

At this point, I've built all but one of the interior four-swirl squares that I need. As I'm finishing two border pieces, I'm cleaning up and assembling pieces in sets of 4. (The final quilt will be a 6x10 grid, with a potential border.) Last night, I completed my first full-width section of the quilt top, and spent much time standing in front of it this morning, giggling. It works. It really works! Finishing the swirls, instead of cutting them off, was absolutely the right choice for this top, and the border pieces sew up a little bit faster because I'm doing fewer seams. I'm thinking a thin green border followed by more white to set it off will be just the trick.

It's a green octopus fabric, made for someone who loves all things octopus and squid. It took about five seconds to name it "Octopus's Garden." A few weeks later, I looked at the selvage of the fabric and learned, to my amusement, that my source fabric's name was "Octo Garden." Clearly, the theme was there all along, just waiting for me to spot it.

I anticipate I'll update this post with a couple more photos; only through writing it did I realize that I've not photographed the process of nailing down the center point of each piece, nor the process of marking it to get a perfectly aligned square. It occurs to me that The Boy will be over on Saturday, and I could probably plop a camera in his hands and let him get the action shots while I work. No point holding this post back any longer, though.

If you're thinking about doing this pattern, I'd encourage you to give it a try before committing to a full quilt top. This is not a fast pattern, and this is most emphatically not a pattern that tolerates sloppy work. You will have to pay attention. You will have to use good template material. You will need to go slowly.

But going slowly is not hard. Working carefully is not hard. It just means you are careful, considerate, and paying attention. Once you get the hang of the technique, it's actually a surprisingly mindless pattern. It just takes a while. A while. A LONG WHILE. I think the results are worth it, though. This is not a quilt pattern that is easy to ignore; it stands out. It moves. It breathes. It cries out for bold, simple color choices.

I hope there will eventually be more quilts made with this pattern. Maybe explaining how I did it will encourage someone to try!

- Log in to post comments